A comprehensive analysis of the characteristics, processing methods, industrial applications, and market dynamics in Dak Lak province.

1. Introduction: The Biological and Economic Significance of the Green Coffee Bean

The global coffee industry, a colossal economic engine driven by the consumption of billions of cups daily, rests entirely upon the integrity and potential of a single agricultural product: the green coffee bean. Often perceived merely as the intermediate stage between the harvest and the roaster, the green bean is, in reality, a complex biological entity—a seed encompassing a dense matrix of alkaloids, lipids, carbohydrates, and phenolic compounds. Its quality, determined by the interplay of genetics, terroir, and post-harvest processing, dictates the ultimate value of the finished beverage. This report provides a comprehensive, expert-level examination of the green coffee bean, with a specific, high-resolution focus on the market dynamics, industrial structure, and production realities of Dak Lak province, Vietnam—the world’s epicenter for Robusta production—as of late 2025.

To understand the market status of green coffee in Dak Lak, one must first deconstruct the commodity itself. Green coffee is not a monolith; it is a category defined by biological variance and processing intervention. The distinction between Coffea arabica and Coffea canephora (Robusta) is fundamental, yet within the context of Dak Lak, the conversation is overwhelmingly centered on Robusta. This resilience species, thriving in the basalt red soils of the Central Highlands, contains higher concentrations of caffeine (approximately 2.2% to 2.7%) and chlorogenic acids compared to its Arabica cousin. These chemical attributes are not merely trivia; they are the drivers of the bean’s pest resistance in the field and its functional applications in the nutraceutical industry, where green coffee extract (GCE) has carved out a significant market niche.

The narrative of green coffee is also one of transformation. From the moment the cherry is plucked, the seed undergoes a rigorous sequence of fermentation, drying, and hulling. Each step is a fork in the road for flavor development. The traditional “Natural” process, long the standard for Vietnamese Robusta, is now being challenged and complemented by “Washed” and “Honey” processing methods, driven by a new generation of cooperatives in districts like Krông Năng and cities like Buôn Ma Thuột. These methods are not just technical variations; they represent a strategic shift in the Vietnamese coffee sector’s attempt to move up the value chain, targeting the “Fine Robusta” market where prices can exceed commodity rates by nearly 250%.

As we analyze the market data from December 2025, we observe a sector in a state of high-stakes volatility. With green coffee prices in Dak Lak hovering between 96,400 VND/kg and 97,500 VND/kg , the industry is experiencing a period of historic valuation. This pricing environment, influenced by global futures markets in London and New York, ripples through the local economy, affecting everything from land-use strategies—evidenced by state-owned enterprises diversifying into rice production —to labor contracts and land disputes. This report will dissect these layers, moving from the molecular chemistry of the bean to the macroeconomic levers pulling at the Dak Lak supply chain.

2. Botanical Structure and Chemical Composition

2.1. Anatomy of the Green Bean

The green coffee bean is the endosperm of the coffee cherry (drupe). Structurally, it is designed to nourish the embryo, which sits at the base of the bean. In its raw state, before roasting, the bean is a hard, dense seed, typically varying in color from slate grey to blue-green depending on the origin and moisture content. The preservation of this embryo is critical; although the bean is “dormant” during storage, it must remain viable to retain its flavor potential. The death of the embryo, often caused by excessive drying or high storage temperatures, leads to the breakdown of enzymatic activity and the onset of “woody” or “flat” flavors.

Surrounding the endosperm is the spermoderm, commonly known as the “silver skin.” In polished green beans, much of this silver skin is removed, but remnants often remain tucked in the center cut. In the context of processing, the removal of the layers above the silver skin—the parchment (endocarp), mucilage (mesocarp), and skin (exocarp)—defines the category of the green bean.

2.2. Phytochemical Profile and Bioactivity

The commercial and nutritional interest in green coffee stems from its rich chemical profile, which differs significantly from roasted coffee. The roasting process is a pyrolytic event that degrades thermolabile compounds; therefore, the green bean serves as the primary source for specific bioactive phytochemicals.

2.2.1. Chlorogenic Acids (CGAs)

Green coffee beans are among the most abundant dietary sources of chlorogenic acids, a family of esters formed between quinic acid and certain trans-cinnamic acids, most notably caffeic acid.

- Concentration: In green Robusta beans cultivated in Dak Lak, CGA content can be exceptionally high, acting as a natural defense mechanism against herbivores and microbes.

- Thermal Instability: Research indicates that roasting destroys a significant portion of the CGA content. As the bean temperature rises, CGAs hydrolyze or lactonize into quinolactones, which contribute to the bitterness of the roast but diminish the antioxidant capacity associated with the raw bean. Consequently, for health applications targeting antioxidant intake or blood pressure regulation, the green bean is the requisite raw material.

Metabolic Impact: CGAs are hypothesized to inhibit the enzyme glucose-6-phosphatase, which regulates the release of glucose from the liver into the bloodstream. This mechanism is the basis for the widespread use of green coffee extracts in weight management supplements, as it may reduce carbohydrate absorption and modulate blood sugar levels.

2.2.2. Alkaloids: Caffeine and Trigonelline

- Caffeine: A methylxanthine alkaloid, caffeine is stable during roasting, meaning the caffeine content of a green bean is roughly equivalent to that of a roasted bean by weight (though volume changes during roasting affect this ratio in the cup). In Dak Lak’s Robusta, caffeine content is high, contributing to the “strong” character of the region’s coffee and its use in high-intensity instant coffee blends.

- Trigonelline: This alkaloid contributes to the bitterness of green coffee but degrades during roasting to form nicotinic acid (Vitamin B3) and diverse volatile aromatics like pyridines and pyrroles, which are essential to the roasted coffee aroma.

2.2.3. Lipids and Waxes

The lipid fraction of the green bean is primarily located in the endosperm and is composed of triglycerides, sterols, and tocopherols.

- Coffee Oil: This oil is extracted for use in the cosmetic and food industries. It contains diterpenes such as cafestol and kahweol, which have been studied for both their anti-inflammatory properties and their hypercholesterolemic (cholesterol-raising) effects.

Surface Waxes: The outer layer of the bean contains carboxylic acid-5-hydroxytryptamides (C-5HT), also known as coffee waxes. These compounds are naturally present in the cuticle. While they have antioxidant properties, they are also correlated with stomach irritation in sensitive individuals. Some advanced post-harvest processes, such as fermentative wet processing using Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast, have been developed to reduce the levels of C-5HT and diterpenes, creating “stomach-friendly” green coffee variants.

3. Post-Harvest Processing: The genesis of Flavor and Market Value

The transition from a ripe coffee cherry to a stable, tradeable green bean is achieved through processing. In Vietnam, and specifically in the diverse microclimates of Dak Lak, processing methods are evolving. While the traditional dry method dominates the commodity sector, the pursuit of higher value has led to the adoption of wet and semi-wet methods. These processes do not merely remove the fruit; they fundamentally alter the chemical composition and sensory profile of the green bean.

3.1. The Natural (Dry) Process: Tradition and Body

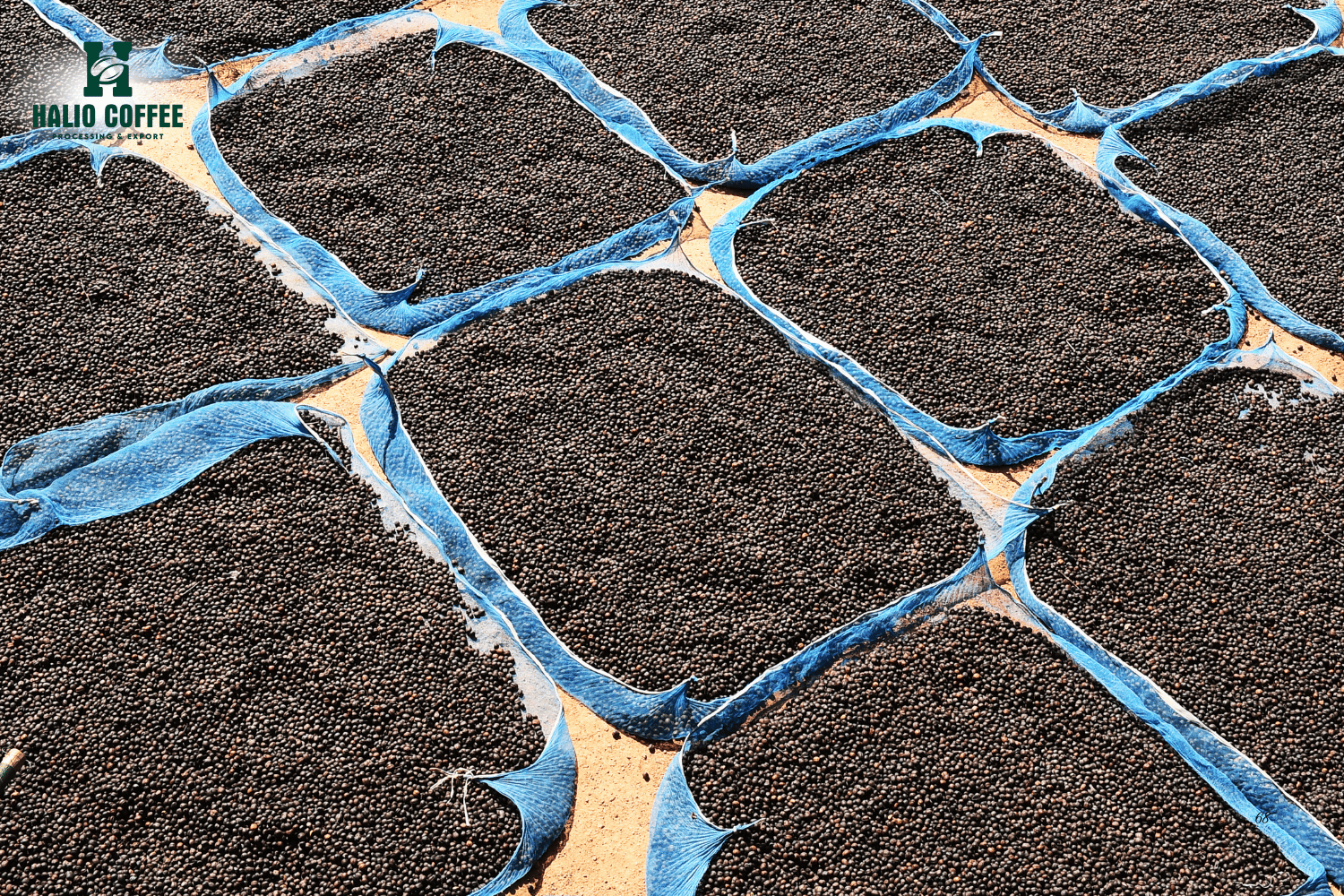

The Natural process, also known as the Dry process, is the oldest and most straightforward method, historically favored in the Robusta belts of Vietnam due to its minimal water requirements.

- Mechanism: The entire coffee cherry—skin, pulp, and seed—is harvested and spread out to dry on patios or raised beds. The drying process can take weeks. During this time, the fruit flesh ferments slightly and dehydrates, causing the sugars and mucilage to adhere to the parchment layer surrounding the seed.

Sensory Outcome: This prolonged contact between seed and fruit allows for the migration of sugars and soluble solids into the bean. The resulting green beans, when roasted, produce a coffee with a heavy body, lower acidity, and intense sweetness. Flavor notes often veer towards earthy, chocolate, and nutty profiles, sometimes developing unique fruity notes like berry or dried apple.

Risks and Challenges: The Natural process is fraught with risk. Because the fruit is intact, the drying must be uniform. If the layer of cherries is too thick or if rain occurs, uncontrolled fermentation can set in, leading to mold growth and “off” flavors described as distinct defects in TCVN standards. Furthermore, weather conditions heavily influence the consistency of the final product, leading to variability in taste from lot to lot.

- Commercial Status: This remains the backbone of the industrial Robusta market in Dak Lak, feeding the massive demand for instant coffee production where body is prized over acidity.

3.2. The Washed (Wet) Process: Precision and Acidity

The Washed process stands in direct contrast to the Natural method, focusing on removing the fruit influence to reveal the intrinsic flavor of the seed.

- Mechanism: Immediately after harvest, the cherries are mechanically depulped to remove the skin. The beans, still coated in sticky mucilage, are then submerged in water tanks for fermentation. This fermentation breaks down the pectin in the mucilage, allowing it to be washed away completely. The clean parchment coffee is then dried.

Sensory Outcome: Washed coffees are characterized by a “clean” presentation of flavors. Without the masking effect of the fruit sugar, the acidity is higher—described as bright, lively, or fresh. The flavor profile often highlights floral notes and specific fruit tones (e.g., citrus, stone fruit) inherent to the genetics of the plant.

Operational Context: This method is resource-intensive, requiring significant water and waste-water treatment infrastructure. In Dak Lak, it is less common for commodity Robusta but is increasingly used for high-grade lots intended for the specialty market. The removal of the fruit flesh means producers cannot rely on external sugars to mask defects, making this a “transparent” process that exposes the true quality of the bean.

3.3. The Honey (Semi-Washed) Process: The Middle Path

The Honey process has emerged as a compelling hybrid, gaining traction among progressive cooperatives in districts like Krông Năng (e.g., Ea Tan Cooperative).

- Mechanism: The cherries are depulped to remove the skin, similar to the Washed process. However, the mucilage is not washed off. Instead, the beans are dried with the sticky mucilage still attached. The term “Honey” refers to the texture of this sticky layer, not the addition of honey.

Variations: Producers control the intensity of the process by adjusting the amount of mucilage left on the bean and the drying time, leading to sub-categories like White, Yellow, Red, and Black Honey.

Sensory Outcome: Honey processed green beans occupy a sensory middle ground. They possess the sweetness and complex body of a Natural due to the prolonged contact with the mucilage sugars, but they retain some of the acidity and clarity of a Washed coffee. They are often described as “balanced,” with a potential to highlight both fruity and clean flavors.

Economic and Environmental Implications: The Honey process uses significantly less water than the Washed process, making it an eco-friendly alternative for regions facing water scarcity. However, it is labor-intensive. The drying beans must be turned frequently to prevent the sticky mucilage from clumping or molding. This requires precise management; improper handling can lead to defects just as easily as in the Natural process.

Roasting Implications: Green beans processed via the Honey method often have a higher sugar content in the outer layers. Roasters must be cautious, as these sugars can caramelize and burn quickly in the roaster, necessitating a different heat profile compared to Washed beans.

3.4. Comparative Overview of Processing Methods

| Feature | Natural (Dry) | Washed (Wet) | Honey (Semi-Washed) |

| Input Material | Whole Coffee Cherry | Depulped & Demucilaged Bean | Depulped Bean with Mucilage |

| Water Consumption | Low | High | Moderate |

| Drying Time | Long (Weeks) | Moderate | Moderate to Long |

| Risk Profile | High (Mold/Fermentation) | Low (Controlled) | Moderate (Mucilage Mgmt) |

| Body (Mouthfeel) | Heavy, Full | Light, Tea-like | Creamy, Medium-Full |

| Acidity | Low, Muted | High, Bright, Lively | Medium, Balanced |

| Flavor Notes | Earthy, Chocolate, Berry, Winey | Citrus, Floral, Stone Fruit | Sweet, Jammy, Balanced |

| Dak Lak Market Niche | Commodity & Instant Coffee | Specialty Arabica/Fine Robusta | Emerging Fine Robusta |

4. Standardization, Grading, and Quality Assurance: TCVN 4193:2014

In the international trade of green coffee, standardization is the language of value. For Vietnam, the definitive regulatory framework is TCVN 4193:2014, a national standard that aligns with ISO protocols to grade green coffee based on physical and sensory attributes. Understanding this standard is crucial for navigating the Dak Lak market, as it dictates the difference between a “Grade 1” export lot and “Off Grade” material.

4.1. The Grading Matrix

The TCVN 4193:2014 standard evaluates green coffee on three primary axes: Screen Size, Defect Count, and Moisture Content.

4.1.1. Screen Sizing (Determination of Bean Size)

Coffee beans are sized using screens with round holes, measured in increments of 1/64th of an inch. Sizing is vital because uniform beans roast more evenly; a mix of large and small beans would result in some being burnt while others are under-roasted.

- Robusta Grades:

- Grade R118: Requires 90% of the beans to remain on Screen No. 18 (7.10 mm). This is a premium large-bean grade.

- Grade R116: Requires 90% of the beans to remain on Screen No. 16 (6.30 mm). This is a standard export grade.

- Grade R13: A smaller bean grade, often used for lower-cost blends or soluble coffee production.

Methodology: The sieving process is strictly controlled (TCVN 4807:2013/ISO 4150:2011) to ensure reproducibility between the seller in Dak Lak and the buyer in London or Hamburg.

4.1.2. Defect Counting and Scoring

The visual quality of the bean is assessed by counting “defects” in a 300g sample. The standard uses a weighting system where different imperfections carry different penalties.

- Primary Defects: These are severe flaws that significantly impact the cup taste.

- Black Beans: A bean that is more than 50% black externally or internally. This is often caused by severe fermentation or fungal infection. One black bean typically counts as one full defect.

- Moldy Beans: Signs of fungal growth. Highly penalized due to the risk of ochratoxin A.

- Foreign Matter: Sticks, stones, or other non-coffee debris.

Secondary Defects: Less severe flaws.

- Broken Beans: Beans that are chipped or cut. It may take several broken beans (e.g., 5) to equal one “full defect” score.

- Insect Damaged: Beans with boreholes from the coffee berry borer.

Grading Limits:

- A Grade 1 lot is strictly limited in its defect count (e.g., often max 60 defects for standard grades, or fewer for premium specs).

- Off Grade: Any lot exceeding the defect limit (e.g., >86 defects) is classified as off-grade and usually sold at a steep discount for soluble processing.

Foreign Defects: Vietnamese standards generally align with Brazilian legislation, allowing a maximum of 1% foreign defects in certain grades.

4.1.3. Moisture Content

Water activity is the enemy of stability. TCVN 4193:2014 mandates a moisture content between 9% and 13%.

- Lower Limit (9%): Below this level, the bean becomes brittle and the embryo dies, leading to rapid flavor fading and “woody” notes.

- Upper Limit (13%): Above this level, the risk of fungal proliferation is extreme, particularly in the humid climate of Dak Lak. Wet beans can ferment in the bag, developing “sour” or “phenolic” taints that render the coffee undrinkable.

4.2. Sensory and Visual Assessment

Beyond the mechanical metrics, the standard references TCVN 4808:2007 for visual inspection. High-quality green coffee should have a uniform color—typically blue-green or grey-green for wet-processed and natural Robusta respectively. “Brown” or “faded” beans are indicators of old crop or improper storage conditions (high humidity). While TCVN 4193 focuses on physical grading, the emerging “Fine Robusta” movement layers the SCA (Specialty Coffee Association) cupping protocols on top of this, seeking coffees that score above 80 points on a sensory scale, free from primary defects and showcasing unique positive attributes.

5. The Chemistry of Roasting and The Home Roasting Culture

The primary industrial use of green coffee is roasting—the thermodynamic process that transforms the chemical precursors in the seed into the complex flavor compounds of the beverage. However, a growing sub-market of home roasters is engaging with green coffee directly, driven by the desire for freshness and customization.

5.1. The Roasting Process: A Chemical Drama

Roasting is not merely cooking; it is a sequence of distinct chemical phases.

- Drying Phase: As the green beans (10-12% moisture) are heated, the water evaporates. The beans turn from green to yellow and smell like grass or hay.

- The Maillard Reaction: As temperatures rise (approx. 150°C), amino acids and reducing sugars react. This non-enzymatic browning creates hundreds of volatile aromatic compounds (nutty, bready, savory notes) and melanoidins, which give roasted coffee its brown color and body.

- First Crack (approx. 196°C): This is a critical auditory cue for roasters. The buildup of steam pressure and CO2 within the cellular matrix of the bean eventually exceeds the structural integrity of the cellulose walls. The bean fractures with a “pop” sound, similar to snapping twigs.

- Flavor Profile: Stopping the roast shortly after the first crack results in a “Light Roast.” This preserves the enzymatic flavors (fruit, floral) and high acidity.

Second Crack (approx. 224°C): If heating continues, the cellulose matrix fractures further, releasing oils to the surface. The sound is a faster, quieter “snap” (like Rice Krispies).

- Flavor Profile: This marks the territory of “Dark Roast.” The flavors are now dominated by the distillation of the bean material (carbonization), resulting in smoky, bitter, and chocolatey notes. The body is fuller, but the origin character is largely obscured.

5.2. Home Roasting Methods and Equipment

The availability of green beans has democratized roasting. Enthusiasts use various methods, each with specific heat transfer characteristics.

- Pan Roasting (Conduction): The most primitive method involves a skillet or wok. It relies on conductive heat (direct contact).

- Pros: Minimal equipment.

- Cons: Highly uneven. Beans can scorch on the outside while remaining raw inside. It requires constant agitation.

Popcorn Poppers (Convection): Electric hot-air corn poppers are a favorite entry point for home roasters.

- Mechanism: They function as “fluid bed” roasters. A stream of hot air lofts and agitates the beans, ensuring very even convective heating.

Limitations: Batch sizes are small (approx. 3-4oz). The roast is often very fast (4-6 minutes) due to the high efficiency of heat transfer, which can sometimes lead to a lack of flavor complexity compared to slower drum roasts.

Bread Machines and Heat Guns: A “hack” method where a bread machine provides agitation (stirring) while a handheld heat gun provides the thermal energy. This allows for larger batches and manual temperature profiling.

Scalability Debate: While these methods are excellent for learning, critics argue they lack scalability and repeatability compared to dedicated drum roasters (e.g., Behmor, Gene Cafe) which offer precise control over variables like airflow and drum speed.

6. Green Coffee Extracts: The Nutraceutical Frontier

Beyond the roaster, green coffee has found a lucrative application in the nutraceutical and pharmaceutical sectors. The demand for Green Coffee Extract (GCE) is driven by the preservation of bioactive compounds that are otherwise destroyed by roasting.

6.1. Extraction Technologies

The goal of GCE production is to isolate target molecules—primarily chlorogenic acids and caffeine—while removing fibrous material.

- Solvent Extraction: Industrial methods often utilize solvents. A common technique involves a mixed solvent of naphtha (to remove lipids) and ethanol (to extract phenolics). This creates a concentrated powder.

Water Extraction (Swiss Water Style): For “clean label” products and decaffeination, water is used as the solvent. Green beans are soaked in hot water to dissolve caffeine and flavor solids. The water is then passed through carbon filters to trap caffeine molecules while letting flavor compounds pass through. This “flavor-charged” water is then used to wash new batches of beans, extracting only the caffeine via diffusion gradients.

Supercritical CO2: A high-tech method where CO2 is pressurized to a supercritical state (acting as both liquid and gas). It is highly selective for caffeine and leaves no toxic residues, though it is expensive.

6.2. Health Claims and Clinical Evidence

The marketing of GCE often centers on weight loss and metabolic health.

- Weight Management: The “chlorogenic acid hypothesis” suggests that GCE aids weight loss by reducing the absorption of carbohydrates in the digestive tract and improving glucose metabolism. Some studies have shown significant improvements in fasting blood sugar and waist circumference in subjects taking 400mg of GCE daily.

Cardiovascular Health: The antioxidant properties of GCE may improve blood vessel function, potentially lowering blood pressure.

Skepticism and Dosage: While promising, the medical community notes that “no good scientific evidence” exists to definitively support many of the broader claims (e.g., curing diabetes or Alzheimer’s). The effectiveness is dose-dependent, with studies using ranges from 200mg to 1000mg daily.

6.3. Safety and Side Effects

Green coffee is not inert. It is a potent biological substance.

- Caffeine Sensitivity: Even though GCE contains less caffeine than roasted coffee by volume (sometimes 25-50% less per cup equivalent), high doses can still cause anxiety, jitters, rapid heartbeat, and insomnia.

Gastrointestinal Issues: The high acidity and specific waxes (C-5HT) in green coffee can cause stomach upset, nausea, and diarrhea.

Drug Interactions: GCE may interact with medications for diabetes and blood pressure, necessitating consultation with healthcare providers.

7. The Dak Lak Market: Status and Dynamics (December 2025)

Dak Lak is the beating heart of Vietnam’s coffee industry, accounting for a massive share of the country’s Robusta output. As of December 2025, the market is characterized by historic price levels, shifting institutional structures, and a strategic battle between quantity and quality.

7.1. Price Trends and Market Volatility

The market data from late December 2025 reveals a scenario of intense bullishness.

- Historic Highs: Transaction prices for green coffee (cà phê nhân xô) in Dak Lak are recorded between 96,400 VND/kg and 97,500 VND/kg. To contextualize, this is a profound increase from historical averages, driven by global supply constraints and the increasing reliance on Robusta in global blends.

Intra-Day Volatility: The market is highly sensitive. Reports indicate price jumps of 900 to 1,000 VND/kg within single trading sessions (e.g., from Dec 30 to Dec 31). This volatility reflects the tethering of local prices to the London (Robusta) and New York (Arabica) futures exchanges. When the London floor rises, the collection agents in Ea Kar and Buôn Ma Thuột immediately adjust their “board prices.”

Regional Variance: Prices are not uniform.

- Dak Lak (General): ~97,300 VND/kg.

- Dak Nông: ~97,500 VND/kg (slightly higher, possibly due to logistics or local competition).

- Lam Dong: ~95,700 VND/kg (typically lower). This pricing structure creates arbitrage opportunities and intense competition among local collectors to secure stocks from farmers.

7.2. Harvest Seasonality and Supply Flow

The liquidity of the green coffee market is dictated by the harvest cycle.

- The Season: In Dak Lak, the harvest typically runs from late October through December, peaking in November.

Current Context (Dec 2025): By late December, the harvest is largely concluded in lower elevations and winding down in higher areas. Typically, the influx of new crop (supply glut) suppresses prices. The fact that prices remain near record highs (97k VND) during the harvest peak indicates exceptionally strong demand or a disappointing yield (possibly due to climate factors like drought), leading exporters to bid aggressively to fill contracts.

7.3. The Institutional Landscape: Giants and Collectives

The Dak Lak coffee sector is a tapestry of state power and cooperative innovation.

7.3.1. State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) and Large Corporations

- Simexco Daklak: Located in Buôn Ma Thuột, Simexco is a titan of the industry, with export turnovers exceeding $1 billion USD. They act as a stabilizing force, implementing sustainable supply chains and acting as a primary gateway for Dak Lak coffee to reach the EU and US markets.

Vinacafe Subsidiaries (The 7-Series Companies): These entities, remnants of the state plantation system, are in transition.

- Company 719 (Ea Kar/Krong Pac): This company highlights the friction of modernizing agrarian relations. It is currently embroiled in legal conflicts regarding “contract farming” (khoán). Farmers (receiving land to farm in exchange for product delivery) have disputed contract terms, leading to “coercive” enforcement measures. This underscores the difficulty of managing the landlord-tenant relationship in a volatile market where farmers might prefer selling to private traders for immediate cash rather than fulfilling state quotas.

Company 721 (Ea Kar): In a fascinating strategic pivot, this coffee company has aggressively diversified into rice production, marketing ST24 and ST25 (World’s Best Rice) varieties under the brand “Gạo Bảy Hai Mốt”. This signals that for some state entities, green coffee is no longer the sole basket; diversification is the new survival strategy.

Company 720 (Ea Kar): Continues to operate in the traditional coffee sector in Cư Ni commune.

7.3.2. The Cooperative Movement and “Fine Robusta”

A vibrant layer of cooperatives is emerging, driven by the need to escape the commodity price trap.

- Ea Tan Cooperative (Krông Năng): This group is a pioneer in the “Fine Robusta” movement. By adopting Honey and Natural processing methods, they produce specialty lots that sell for 250,000 VND/kg—a staggering premium over the 97,000 VND/kg commodity price. This price differential validates the economic argument for quality over quantity.

Ea Tu Cooperative (Buôn Ma Thuột): Operating with Fairtrade certifications, they link directly with foreign exporters like Dakman. This allows them to pay their farmer members a premium of 2,000 to 2,500 VND/kg above the market rate, creating a loyalty loop that ensures consistent supply.

Other Players: Cooperatives like Minh Tan Dat (Ea Kmút) and Quang Tien are building new infrastructure (offices, processing yards) to formalize their operations and aggregate power.

7.3.3. Private Aggregators

Companies like La Hai Linh (Ea Kar) serve the essential function of liquidity providers. As registered buyers of agricultural produce, they bridge the gap between smallholder farmers and the large export houses, handling the logistics of collection and initial quality sorting.

8. Storage and Logistics in a Tropical Climate

The journey of the green bean does not end at processing; it must survive storage. Dak Lak’s climate—hot and humid—poses a severe threat to green coffee quality.

- Hygroscopic Vulnerability: Green beans are hygroscopic. If the relative humidity (RH) in the warehouse exceeds 60%, the beans will absorb moisture from the air. This pushes their moisture content above the safe 13% limit, reactivating water activity.

The “Fade”: Moisture absorption leads to the “fading” of enzyme activity and the bleaching of color. The cup profile becomes flat and woody. In worse scenarios, it leads to mold growth.

Mitigation Strategies:

- Hermetic Storage: The industry is increasingly adopting hermetic liners (e.g., GrainPro or Ecotact). These plastic liners create a gas-tight barrier inside the traditional jute bag, locking in the bean’s moisture and locking out the ambient humidity.

Palletizing: Bags must be stored on pallets, at least 30cm away from walls, to allow airflow and prevent the wicking of moisture from concrete floors.

Ventilation: Warehouses must be ventilated to prevent heat buildup, as high temperatures accelerate the chemical aging of the bean.

9. Conclusion

The green coffee bean sector in Dak Lak is a study in contrasts and evolution. It is a market where traditional commodity dynamics—driven by global futures exchanges and state-owned enterprises—collide with a burgeoning specialty movement led by innovative cooperatives. The bean itself is being reimagined: no longer just a raw material for caffeine delivery, it is treated as a complex carrier of flavor (via Honey/Natural processing) and a source of potent bioactive compounds (for the extract market).

As of late 2025, the high price of green coffee offers a window of prosperity for Dak Lak’s farmers, but it comes with the volatility inherent in global commodities. The future of the sector lies in the strategies observed in Ea Tan and Ea Tu: differentiating the product through processing excellence (Fine Robusta) and certification (Fairtrade) to decouple local incomes from the fluctuations of the London floor. Whether destined for a high-tech extraction facility, a home roaster’s popcorn popper, or a traditional phin filter, the green coffee bean remains the indispensable currency of the Central Highlands.

- A Consultant’s Master Guide to Communication with Vietnamese Suppliers

- From Bean to Brand: A Strategic Sourcing Guide to Roasted Arabica Coffee for Cafes

- Dry Processed Robusta Beans: An Industry Guide for Producers, Roasters, and Global Distributors

- The Raw Asset: A 2026 Strategic Guide to Sourcing Unroasted Coffee

- The Visibility Playbook: A Consultant’s Guide to Tracking Coffee Shipments from Vietnam