Mastering the Art of Building Relationships with Coffee Farmers in Vietnam

In the complex supply chain of green coffee, the ultimate test of a strategic partnership lies in its human foundation. You have already mastered the operational layer, ensuring seamless post-transactional excellence through expert After-sales support from coffee suppliers. You know the importance of technical assistance, claims resolution, and proactive quality defense.

However, the most resilient supply chains—the ones that withstand market crashes, climate shocks, and quality fluctuations—are not built on legal documents alone. They are built on mutual investment, shared trust, and direct dialogue with the people who manage the soil.

This is the strategic imperative of building relationships with coffee farmers.

For the Vietnamese green coffee beans supplier, this is a commitment to direct trade ethics and sustainable sourcing. For the global buyer, this is the most effective form of risk mitigation. A relationship with a farmer ensures price loyalty during a market spike, quality consistency during a poor harvest, and, most importantly, provides an authentic, high-value story for your retail brand.

This guide is your executive framework for moving beyond the transactional model of the commodity trade and establishing deep, equitable partnerships in Vietnam’s Central Highlands. We will analyze the cultural nuances, the economic levers, and the practical infrastructure required to achieve true collaboration.

Phase I: The Economic Imperative of Direct Engagement

Why should a professional buyer invest time and capital in building relationships with coffee farmers when they can simply buy from a large, consolidated exporter? The answer lies in the concept of shared value.

1. The Loyalty Shield (Price Risk Mitigation)

In a market defined by the C-Price (Futures), farmer loyalty is the ultimate hedge.

- The Problem: When the London Robusta price spikes, farmers often engage in breaching (selling reserved stock to the highest spot bidder), leaving the contracted supplier short.

- The Solution: A direct relationship provides a “Loyalty Premium”—a guaranteed price paid consistently above the market rate. This investment acts as an insurance policy. The farmer knows that in the years the market crashes, the buyer will still be there, honoring the contract. This trust is worth more than a short-term price spike.

2. Quality Control at the Root

The single most important QC parameter—the Ripe Cherry Rate—occurs at the farm level.

- The Challenge: To achieve high-quality lots (like the specialty Honey or Washed Robusta from Dak Lak), farmers must manually select only ripe cherries, which is time-consuming and labor-intensive.

- The Partnership Model: The buyer (via the Vietnamese green coffee beans supplier) provides technical assistance (agronomy training) and invests in equipment (like simple floating tanks or depulpers) in exchange for the farmer’s commitment to quality protocols (e.g., 98% Ripe Cherry Rate). This moves the quality control upstream, reducing the defect count that the supplier has to sort out later.

3. Traceability as a Competitive Edge

A certificate of origin proves the coffee came from Vietnam. A relationship proves it came from Mr. Hùng’s 2-hectare plot in Krông Bông.

- The Value: This traceability is essential for marketing. Today’s consumer demands to know the origin story. The relationship creates content, authenticity, and a premium market position.

Phase II: The Operational and Cultural Framework

Building relationships with coffee farmers in Vietnam requires respect for local cultural values and structural realities, particularly the concept of Quan Hệ (relationship/trust) and the dominance of the smallholder model.

1. The Supplier as the Bridge (The Intermediary Role)

For large international roasters, negotiating directly with thousands of small, fragmented farmers is logistically impossible. The Vietnamese green coffee beans supplier (like Halio Coffee Co., Ltd) must act as the essential intermediary.

- The Strategy: Use your supplier’s local knowledge. The relationship is between Buyer (You) ↔ Supplier (Halio) ↔ Farmer (Community). The supplier manages the daily complexity (logistics, language, local currency), but you must show your face and commitment to the farmer.

- The Action: When visiting the supplier’s facility (193/26 Nguyen Van Cu, Tan Lap Ward, Dak Lak), dedicate time to visit the actual farm plots. Your presence validates the supplier’s commitment to the farmer.

2. The Language of Shared Risk

In the Central Highlands, coffee is a family’s income source, not just a crop.

- The Problem: When weather hits (e.g., the 2023 droughts or 2024 typhoons), the farmer’s priority is survival, not contract adherence.

- The Solution: A true partner participates in the risk. This might mean pre-financing inputs (fertilizer, irrigation), offering crop insurance, or agreeing to a flexible “yield reduction” clause in the contract after a natural disaster.

3. Supporting the Next Generation

Coffee farming is hard work, and in Vietnam, many young people leave the land for city jobs.

- The Action: Investment in the local community—funding scholarships for farmers’ children, building communal drying patios, or improving local infrastructure—is often the most effective way of building relationships with coffee farmers. This long-term investment secures the labor force for your supply chain decades into the future.

Phase III: The Investment Matrix (Beyond the Financial Premium)

Building relationships with coffee farmers requires investment that goes beyond the cash premium paid per kilogram. These are the non-financial metrics that truly secure loyalty:

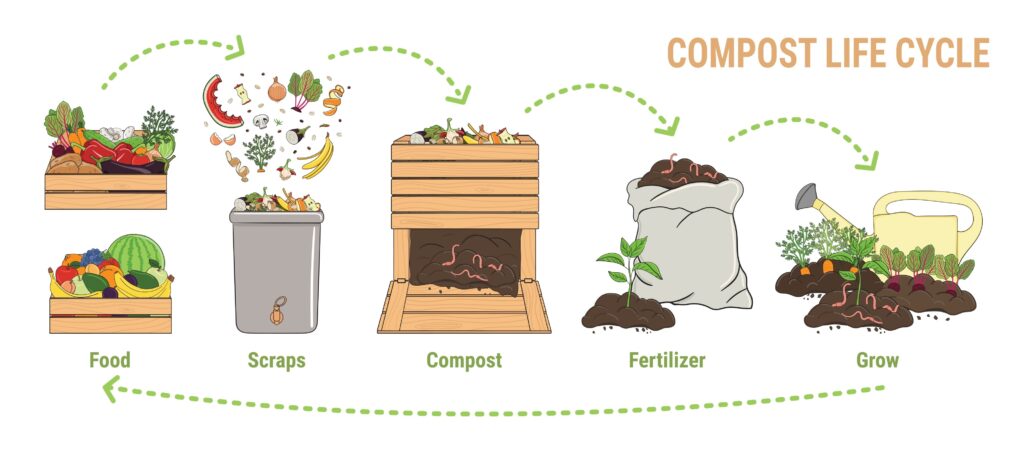

1. The Human Capital Investment (Training)

- The Need: Vietnamese farmers need better knowledge on sustainable practices (pruning, water conservation, composting).

- The Action: The supplier should organize regular training workshops. Example: Focusing on composting techniques to reduce reliance on expensive synthetic fertilizers.

- The ROI: Farmers reduce input costs (making their business more resilient) and improve bean density (improving your quality).

2. The Quality Infrastructure Investment (Shared Assets)

- The Need: Small farmers cannot afford mechanical dryers or raised beds.

- The Action: The buyer (via the supplier) funds the purchase of shared assets for the cooperative.

- The ROI: You secure better quality control at the source. For example, funding a washing station allows the farmer to produce “Washed Robusta,” a higher-value product that requires strict cleanliness—a standard that flows directly to the buyer’s benefit.

3. Direct Feedback Loop (Closing the Gap)

The farmer often has no idea what their coffee tastes like. They sell cherry; they never taste the final roasted product.

- The Action: Send the farmer a box of the final retail product packaged with their story. Provide regular Quality Reports (cupping scores, defect counts) translated into Vietnamese.

- The Value: This completes the ethical circle. It shows the farmer the value of their labor and incentivizes them to improve the specific attributes (e.g., sweetness, cleanliness) that the international market demands.

The Buyer’s Relationship Checklist (The “Trust” Audit)

Before claiming a direct-trade relationship, audit your partnership against these human metrics:

| Relationship Metric | Best Practice (Green Flag) | Red Flag (Sign of Transactional Trade) |

| Visibility | Buyer has physically visited the farm/community in the last 2 years. | Relationship is managed solely by email via a third-party trader in Saigon. |

| Pricing | Contract includes a “Loyalty Premium” paid regardless of market price. | Pricing is strictly C-Market + Differential, renegotiated every quarter. |

| Investment | Supplier provides evidence of community funding (e.g., school funds, processing equipment). | Supplier only offers a discount on the final price. |

| Feedback | Farmers receive annual reports detailing their coffee’s defect rate and cupping score. | Farmer is only told “Your coffee is accepted.” |

| Risk | Contract includes a clause addressing crop loss mitigation (shared risk). | Contract defaults if the supplier experiences Force Majeure. |

Strategic Conclusion: From Customer to Co-Producer

Building relationships with coffee farmers is the highest form of supply chain resilience. It is the ultimate evolution from a transactional approach—where you source raw materials—to a strategic partnership—where you co-produce the final product.

By leveraging a responsible Vietnamese green coffee beans supplier like Halio Coffee to bridge the cultural and logistical gaps, you secure access to the highest quality, lowest-risk physical inventory. You ensure that the money you spend on the bean translates directly into economic stability and environmental stewardship at the source in Dak Lak.

This is the end of the procurement journey. We have sourced the origin, secured the price, established the quality, and built the human foundation.

The final test of this entire strategy is its real-world success. Does this model actually create a profitable product that commands a premium in the global market? To answer this, we must examine the ultimate proof: documented instances of businesses thriving using this comprehensive, relationship-first sourcing model.

Read Next: Case studies of successful coffee partnerships

- Market Outlook 2026-2027: A Strategic Vietnam Green Coffee Bean Price Forecast Europe

- The Gold Standard of Efficiency: A 2026 Strategic Guide to Sourcing Robusta G1 S18

- The Heart of Robusta: A Buyer’s Guide to Vetting Dak Lak Coffee Suppliers

- Deconstructing the Green Coffee Price: A Buyer’s Guide to Sourcing Costs

- Specialty Coffee Beans Vietnam Supplier: Elevating Vietnamese Coffee to Global Standards